FARMINGTON CORNER

A continuing tale of life in the boonies

No. 285

Poets who matter: 1. Omar Khayyam

FARMINGTON – The air of northern Strafford County, this summer, is heavy with the buzzing of bees and the droning of poets, and things are going to get worse before they get better.

While New Hampshire Poetry Society searches for an official state poet, Rochester’s bushes are now being beaten for a city poet laureate, who will soon be crowned by the elite in a dazzle of publicity and flash bulbs, before the general public can express their feelings with a great and prolonged waft of apathy.

Yet poetry can deeply affect lives and give clear voice to clumsy, half-formed thoughts and to stumble on such illuminating verse is one of the joys of life. Let me, a plodding doggerelist, give an example.

I was sitting in the State Bar in Glasgow, Scotland, about 35 years ago, when someone pushed a copy of the Evening Citizen along the counter and stabbed a finger at a news snippet headlined: Coldstream man shoots himself.

"Are you no fae Coldstream?" asked my companion, looking over his beer.

Indeed I was, and I knew the dead man well, having shared a school desk with him for many years as a kid.

The world, I discovered a little later, had closed in on Pete at an early age, and so one evening in one of the village’s eight pubs (Scotland is a drinking nation) he had swallowed a yard of ale in record time, left the premises, walked home and blown himself away with a shotgun. Pete was only 22, and his death deeply affected me.

The village of Coldstream sits on the north bank of the River Tweed that marks the boundary with England, a nation with whom we have been at peace for about 400 years, although you wouldn’t think so when there is an international football match between the two countries.

On the English side of the Tweed, about a mile a way through waving wheat and barley fields is the village of Cornhill, which only has one pub. Being in another country, though, it has different licensing hours, and on a Sunday, back in those days, the hotel would open at noon, whereas the Scottish bars could not start serving until 12:30 p.m.

Thus, on a Sunday morning, from about 11:30 a.m., there would be an exodus of Scottish drinkers with Saturday night hangovers to attend to, heading over the river to get a 30-minute start on the action. My friend Pete was always in the vanguard.

My eulogy for him took the form of sad verses with a lively chorus as compensation. The second verse went so:

To walk across to Cornhill, you aye were fain,

On a Sunday morning, force nine gale and pouring rain,

Such dedication, seldom see the like again,

Peter L---, Peter L---.

The refrain then took over and concluded with a rhyming couplet:

…ladies weep and strong men cry,

He’s with the Great Bartender in the sky.

It was a sincere attempt to immortalize someone who hadn’t lived long enough to be a town worthy, but the words lacked something I could never put my finger on, and the poem never achieved popularity.

Back in the State Bar, a couple of months on, I was discussing the problem with my mentor of those days, Death’s Head Dougie, and he suggested that Edward Fitzgerald’s translation of Omar Khayyam may have covered the topic of drinkers versus the sands of time.

At once, I purchased a boxed copy and, o joy, the third quatrain of the first edition, published in 1859, summed it up:

And, as the Cock crew, those who stood before

The Tavern shouted – "Open then the Door!

You know how little while we have to stay,

And, once departed, may return no more."

Omar Khayyam lived in what is now modern day Iran and his life bridged the 10th and 11th centuries, back before the mullahs really got tough on booze.

His verses, so beautifully interpreted by Fitzgerald, are melancholic, mystical and laced with fatalism. They should bring peace, or at least a measure of comfort, to us all – and yet … and yet!

In Glasgow, I was a police officer, and for several years was assigned the Blackhill beat in the northeast of the city, where a substation had just been opened in the housing project of 5,000 people in the vain hope of subjugating it.

The station was small – it had previously been a candy store - and its conversion had presented several architectural challenges including how to fit five toilets into a confined space – one for the public, one for prisoners, one for policewomen, one for policemen and one for sergeants and upper ranks.

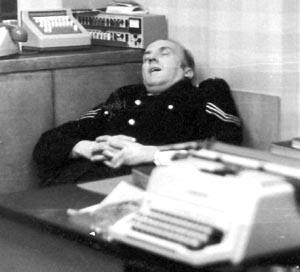

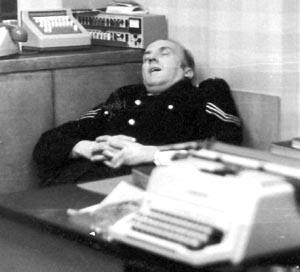

The prisoners’ toilet was in a holding cell whose door opened into a narrow passage leading to a kitchen and other urinary facilities in the rear of the building. The cell’s reinforced observation window looked out onto the office where a desk sergeant typed or, when there was opportunity, dozed.

This arrangement could be particularly irritating to typing or dozing sergeants if the prisoner within the cell elected to flatten their face against the glass and stare into the office.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JOHN NOLAN

Dozing police sergeant. Blackhill substation, Glasgow, Scotland. Circa 1974

AWAKE! for Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight:

And Lo! – the Hunter of the East has caught

The Sultan’s Turret in a Noose of Light.

Omar Khayyam (Quatrain 1, First Edition. Fitzgerald’s translation.)

Often there would be a cry of "Curtains" from the sergeant and a constable would dutifully tear out the stock market pages of a newspaper and tape them, upside down, onto the glass, to frustrate the prisoner’s gaze whilst substituting nothing interesting to read.

A Blackhill prisoner tended not to take this treatment lying down, and might then stand with his back to the wooden door, and thump it over and over with his heel.

In a well-rehearsed maneuver two constables and a sergeant would subsequently rush into the cell and deprive the prisoner of his boots. Sometimes this quieted things, but not always, for persistent types would resume the thumping in their stocking feet.

At this stage, a constable would look expectantly at the sergeant and, given the nod, would retreat back up the corridor to the kitchen, fill up a white porcelain mug with cold water, sneak back down and whisk the icy liquid under the cell door. An anguished cry would result, as water swirled round sock, and a barrage of curses would follow.

"There must be a mellower way," I thought to myself, after witnessing this ritual yet again, and turned to Omar Khayyam for guidance.

Quatrain 51 of the Fitzgerald’s First Edition seemed to provide the answer, with a gentle admonition to accept the cards that life deals out – solace, surely, for any prisoner.

So I now confess, it was me, Constable Nolan, who penciled the following graffiti inside the Blackhill police substation holding cell, before going off duty early one morning in 1974:

The Moving Finger writes; and having writ,

Moves on; nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a word of it.

I came back on duty late the following evening, having quite forgotten about the Khayyam quatrain on the wall.

The station was in chaos. Curtains were taped up over the cell window – an upside-down section on women’s knitting – and a pair of prisoner’s shoes were outside the door, alongside an empty white mug and traces of water.

Within the cell, a furious voice was yelling at the top of its lungs, "F--- YOU PEOPLE. THE MOVING FINGER WRITES AND HAVING WRIT MOVES ON. ALL F---ING RIGHT, PAL. NOR ALL THY PIETY NOR F---ING WIT …"

Uh-oh! Beam me up, Omar.

Aug. 24, 2003