FARMINGTON CORNER

A continuing tale of life in the boonies

No. 286

Poets who matter: 2. John Clare

FARMINGTON – With the twin hunts for Poets Laureate in Rochester and New Hampshire in their final gripping stages, the local populous continues to express its strong feelings on the subject by flocking to watch monster trucks crush scrapped cars – a modern day equivalent of the Roman amphitheatre.

The way to bridge the gap, though, is not for poets to wax all huffy and satirical, like Juvenal, but to wise up and write about topics that move the hoi polloi. Fewer odes to psychological analyses and more tributes to the Flag; less versifying about birds on twigs, more about the heroic exploits of moose hunters.

As recently illustrated in this column with Omar Khayyam, there are poets of the past whose work may still bring joy or comfort to a human breast, and this week, I would humbly draw your attention to John Clare.

He appeals to me, partly because he had strong rural roots and finished up in a lunatic asylum, while I have strong rural roots and wound up, about 30 years ago in … no, not Farmington (that was 20 years ago) … but Blackhill, a Glasgow east-end housing project feared in proximity and derided from a distance by the rest of the city.

I was a police constable dispatched there as a beacon of authority, and as such, had much in common with an old priest who used to flail erring parishioners with a walking stick as he hobbled along the streets, and City Hall’s combative local housing manager. Which brings me at once to Clare and his bitter satire, The Parish:

Churchwardens, constables and overseers

Make up the rounds of commons and of peers;

With learning just enough to sign a name,

And skill sufficient parish rates to frame …

Blackhill consisted of 14 streets and 5,000 people, of whom almost half were registered as Scottish criminals, a surprising number when you consider that almost everyone else was too young to be fingerprinted. The community was both tight-knit and tight-lipped, and until a small police station was opened in the heart of the project, it had governed itself through occasional acts of ruthlessness and savagery, alleviated by day-to-day acts of compassion and darkly humorous tales of caution and exploit.

The houses lay in the shadow of Provan Gas Works, with its great hills of coke, and two enormous metallic grey gas-holders which rose or fell dependant upon the city’s demand for gas. Nearby, a chemical works poured acrid orange fumes over the glass-littered streets when the wind was from the west; a derelict whisky bond provided fuel, one night, for one of Glasgow’s more spectacular fires and charred remains for years after; abandoned railroad tracks snaked and rotted; and a smelly canal fed by a ditched stream (once known as the Molendinar Burn) held green water and the burned and blackened frames of stolen cars.

All nature, save roaming dogs, was banished from this blighted landscape, and on solitary foot patrol, I would divert my thoughts with the help of Clare’s Emmonsail’s Heath in Winter:

I love to see the old heath’s withered brake

Mingle its crimpled leaves with furze and ling

While the old heron from the lonely lake

Starts slow and flaps his melancholy wing …

* * *

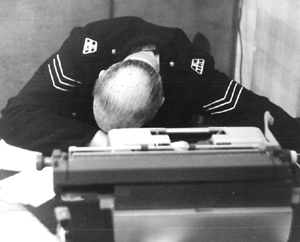

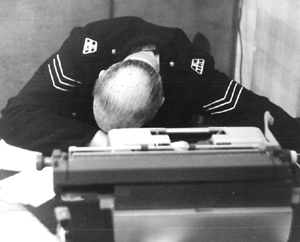

Anyway, back at the ranch, or rather the police substation, an elderly woman pushed her way through the swing doors around 2 a.m. one Saturday, and into the Blackhill office where a sergeant had dozed off over a typewriter.

"My friend has been assaulted," she announced.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JOHN NOLAN

Dozing police sergeant. Blackhill substation, Glasgow, Scotland. Circa 1974

"Loath to ope my sleepy eyes,

Wearly still, in pain to rise ... "

- John Clare

I was on refreshment break, but turned down the heat under a pan of cockaleekie soup, and followed the old one out of the station and up the hill to Hogganfield Street, where she lived, and where her assaulted friend was still located.

During the short journey, the old woman told me that earlier in the evening she, and a male friend, had gone to a pub in the east of Glasgow called the Saracen’s Head, or more familiarly, the Sarry Heid, where a wine-based drink, best-known as white tea (short for White Tornado), could be had at a reasonable price and which produced temporarily pleasing effects. There, the couple had met a stranger and invited her back to Blackhill after pub closing time to share a half bottle of sweet sherry the lady was kind enough to buy them.

While her booze lasted, the stranger’s companions elevated her to the rank of friend, but when the bottle was drained the man of the company, it seems, began to consider her extraneous. Harsh words were spoken and an assault ensued, though not severe enough, my guide estimated, to justify radioing for an ambulance.

The door of the apartment, on the top floor of a three-storey block, was opened cautiously by a thin, stooped man in his 70s.

"Can I help you, officer?" he enquired mildly, with a quizzical look.

"I have reason to believe you may have assaulted somebody," I said in officialese. "Move to the kitchen and stay there."

I walked past him into the living-room and cast astonished eyes on the victim seated in a chair. She was ancient and frail and wearing a wedding dress. As I stood in front of her, she slowly raised her head and with enormous sadness said, "Look what this man has done to me, constable."

Each word was spoken with horrified deliberation in the plummy accent of a lady of breeding from the West End of the city.

I surmised the plight of the poor soul - an alcoholic who had gone through the bulk of her life savings after the death of a husband, and had gradually pawned her clothes and furnishings. Now she was reduced to drinking cheap liquor in lowly parts of the city with volatile companions, while clad in her last remnant, a white dress she had worn on her wedding day.

At least it had been white, until the callous character in the kitchen had emptied a whole bag of coal over her head and put her into a state of catatonic shock.

She hadn’t moved since the appalling act took place. Her skin was totally obscured by black coal dust except for two narrow channels on her face created by streaming tears. There was coal in her hair. Coal filled her chair and covered her feet.

"Look what this man has done to me, constable," the lady repeated.

"That’s no right, so it iznae," the old Hogganfield Street woman interjevted, with conviction.

Perhaps ashamed of her predicament, the genteel woman declined to file charges, so in stern terms I ordered the codger in the kitchen to leave the apartment – "papped him oot" in Glasgow parlance – thus allowing the West End lady to stay for what remained of the night, get cleaned up as best she could and then get a bus across the city come daylight.

* * *

I came on duty again at 9 p.m. that evening and read the police log for the previous 14 hours to catch up with the events of the Saturday. And Blackhill was ever eventful.

An entry caught my eye, and I searched out the full report which revealed that at 8:25 a.m. on Royston Road, a handbag had been snatched from the grasp of an old lady clad in a grubby white wedding dress while she was waiting on a No. 11 bus. No witnesses had come forward.

* * *

I wondered how she had got home, and how she would get through what remained of her life, and then my thoughts drifted to tragic John Clare in Northampton Asylum, where, in periods of clarity, he wrote some of his most wrenching poems, including the bleak I am, which was published in 1865, the year following his death. It begins thus:

I am – yet what I am none cares or knows,

My friends forsake me like a memory lost:

I am the self-consumer of my woes,

They rise and vanish in oblivions host …

Aug. 27, 2003